Architecture and Government

The architecture of the American government began with borrowed buildings, continued with commissions, competitions and expansion, and thrives now, through the General Services Administration (GSA) as a force for design excellence, sustainability, and citizen engagement.

From the dawn of the nation to the mid-1930s, the Treasury Department managed the design, the construction, and oversight of federal buildings. Following a period of transition during World War II, GSA became responsible for both the construction of many new federal buildings and the stewardship of existing buildings, including those considered historically significant.

GSA protects and manages more than 500 historic buildings. The path to that stewardship mirrors the rich, complex nature of federal architecture. Depending on the era, political climate, and budget, the federal government has acted as steward, patron, and building manager, juggling one, two, and sometimes all three of these roles.

Early History

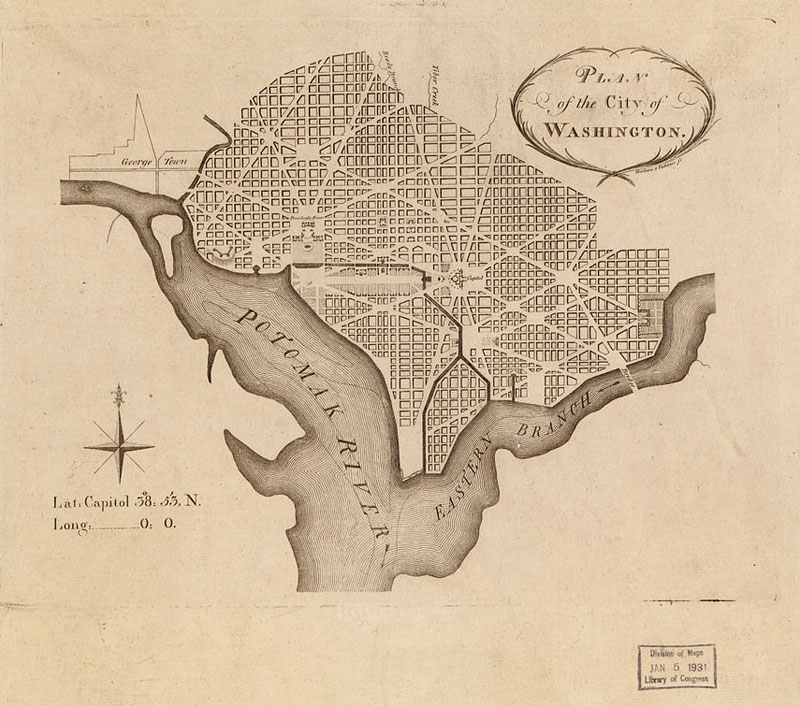

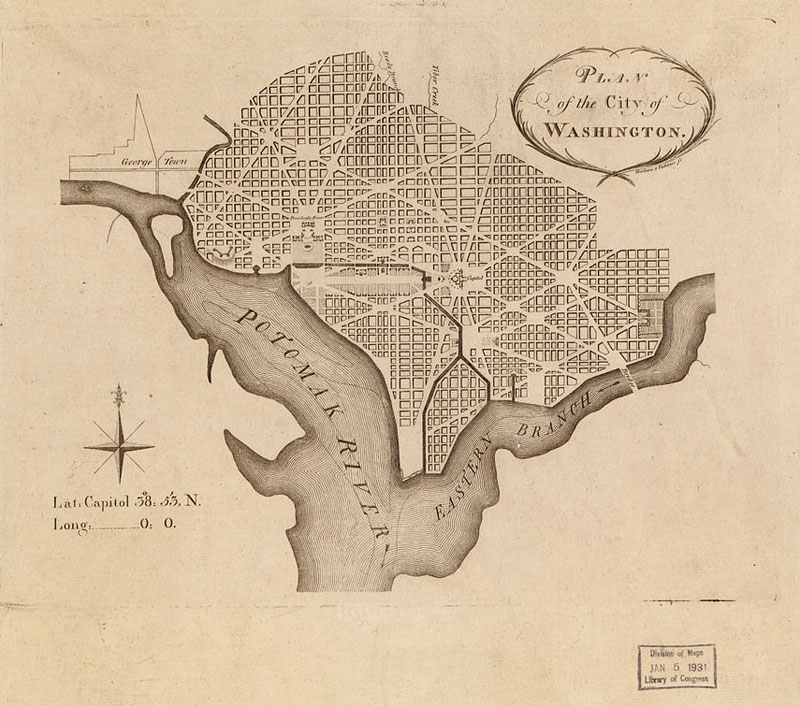

Pierre Charles L’Enfant’s Plan for Washington, D.C., as revised by Andrew Ellicott. Engraved by Thackara & Vallance sc. Photo Credit: Library of Congress.

After the Revolutionary War, the federal government was first based in New York City and then in Philadelphia. George Washington began his presidency in a rented New York City mansion. He finished his term in a stately rented Philadelphia mansion that had once been occupied by British soldiers.

But neither city would end up being the nation’s capital. Finally, in 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, which gave authority to President George Washington to select an exact site for the capital, along the Potomac. The location was challenging, as the area had little infrastructure and few suitable buildings. The act set a deadline of December 1800 for the capital to be ready. In 1792, the act spurred the first major competition to design the President’s House, which was closely overseen by Thomas Jefferson. The winner, James Hoban of South Carolina, received a $500 prize and a gold medal. In 1800, on schedule, President John Adams and his family moved to the completed house.

Treasury Oversight of Federal Buildings

At first, government agencies leased existing structures, rather than building new. For nearly three decades after Washington’s election, the Treasury Department usually repurposed buildings as custom houses, post offices, and courthouses. It was not until 1807 that Congress passed the first legislation to authorize construction of a single federal building in New Orleans, with an appropriation of $20,000 to build either a post office, courthouse, or custom house.

Ten years passed without another construction appropriation. In 1817, Congress earmarked $50,000 for the purchase or erection of suitable buildings for custom houses and public houses in such principal districts of each state where the Treasury secretary deemed it necessary. For perspective, by the end of 1817, the country was made up of 20 states. This was also the year that the President’s House, after nearly being destroyed during the War of 1812, reopened to welcome President James Monroe.

Early Federal Style

The Robert C. McEwen U.S. Custom House, Ogdensburg, NY. Architect: Master Carpenter Daniel W. Church.

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith.

What does early United States architecture look like? The oldest buildings in GSA’s portfolio is the Robert C. McEwen U.S. Custom House, Ogdensburg, NY, a utilitarian 2-story limestone structure built in 1809, which was originally used as a store and warehouse before becoming a custom house.

Between 1780 and 1830, the Federal style of architecture predominated in U.S. public buildings. Developing out of the earlier Georgian style, the Federal style drew inspiration from the monuments of ancient Rome. Common features included symmetry, elliptical fanlights over paneled front doors, elaborate door surrounds, double-hung sash windows, three-part Palladian windows, cornices with dentils or modillions, and graceful decorative ornamentation on mantels, walls, and ceilings.

Today, the oldest buildings in GSA’s inventory are stately but simple custom houses, post offices, and office buildings constructed of brick and stone. Early monumental public buildings possess dignified facades and elegant interior features such as ornamental iron staircases and groin vaulted ceilings, but have minimal public entry space.

By 1830, Greek Revival was the dominant style of American architecture. Authorized by Congress in 1832, the U.S. Custom House in New Bedford, Massachusetts, is the oldest government-constructed building in GSA’s inventory. Its imposing Doric portico and modest interior reflect both the Greek Revival style and the frugality of the federal building program during this era.

Founding the Office of the Supervising Architect

In 1850, according to the census, the United States contained 31 states and four organized territories, with a population of slightly more than 23 million. A federal construction boom began. Between 1850 and 1857, Congress approved $18 million for federal construction. As of December 6, 1853, the government owned and occupied twenty-three buildings, with appropriations for fifteen more authorized.

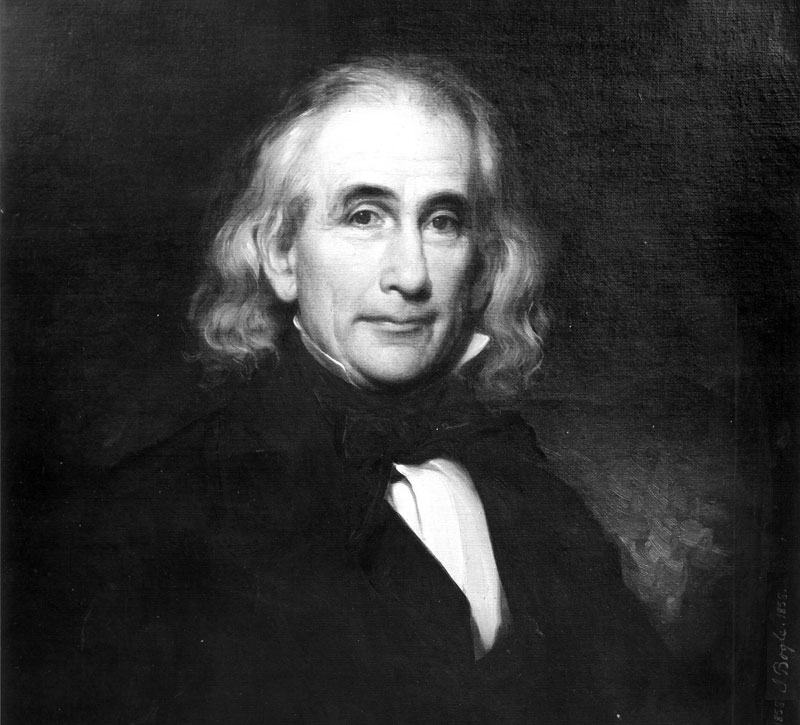

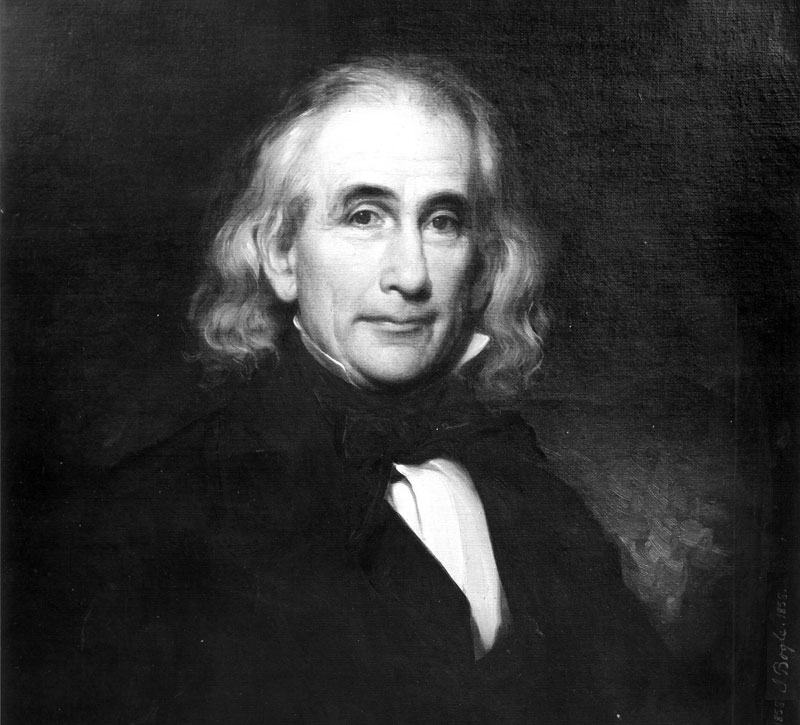

Ammi Burnham Young, Architect and eventual first Supervising Architect of the Treasury Department.

With this expansion of the building program, it became clear that the government needed to centralize design and manage construction of federal buildings in Washington. Previously, federal construction had been administered in the states where the buildings were located, resulting in overruns, faulty construction and design, and poor reporting to Congress. To correct this, the Treasury Department established the Department of Construction in 1852, where a “supervising architect,” Ammi B. Young, joined the staff. Young’s title was simply a designation, not an official title at this point.

When the office was established in 1852, the architectural profession in the U.S. was in its infancy. The nation evolved—sometimes painfully so—and so did federal style. During the Civil War, federal construction of non-military buildings ceased. In 1864, Congress passed an act approving the appointment of a Supervising Architect in the construction branch of the Treasury Department, officially establishing Ammi B. Young’s position. After the Civil War, as the government sought to reunite a divided populace, the Department of the Treasury constructed grand public buildings to express the power and stability of the federal government, an affirmation of unity and strength.

19th Century Styles

The mid-to-late 19th century saw a number of styles of federal architecture come into and sometimes out of favor: Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, Italianate, Romanesque Revival, Renaissance Revival, Second Empire, and Beaux Arts Classicism.

A good example of the grand public building is the State, War and Navy Building, now known as the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building in Washington DC.

The Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Washington DC. A superb example of Second Empire architecture. Alfred B. Mullett, Architect.

Photo Credit: Carol. M. Highsmith.

Construction of the fireproof granite edifice, set on a high platform, with column-enriched entrance pavilions and statuary began in 1871. Architect Alfred B. Mullett designed the building in the Second Empire Style. Popularized in Paris during the reign of Napoleon III, the double-pitched mansard roof became the defining characteristic of the Second Empire style. Beneath the boxy roof line, other building features closely follow the Italianate style and include brackets, paired and hooded windows, and double doors. Unlike the picturesque Gothic Revival and Italianate styles, the Second Empire style was considered very modern. It was used for public buildings constructed during the administration of President Ulysses S. Grant.

When it was completed in 1888, the State, War and Navy Building was the largest office building in Washington. Not everyone fell in love with it, however. When the humorist and novelist Mark Twain tried to describe it, he came up with: “the ugliest building in America.” This kind of complaint is typical of almost any architectural style over time, and federal architecture as a whole was no different. Toward the end of the nineteenth century, sturdy Romanesque post offices and courthouses with campanile towers of rough cut stone, segmental arched entrances, and vast sky-lit work rooms quickly came into, but then went out of, fashion.

Early 20th Century Style

The interior rotunda of the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House, New York, NY. Beaux Arts style at its finest. Cass Gilbert, Architect.

Influences on early 20th-century federal architecture included the World’s Columbian Exposition, held in Chicago in 1893, which featured classical pavilions glowing in Edison’s new electric lights. The impact of the exposition spurred the City Beautiful movement that substantially shaped the government’s approach to public building until after World War II.

City Beautiful principles focused on monumental structures, landscaping, and beautification in the belief that they would create social order and harmony. Among its practitioners was Cass Gilbert, designer of the Alexander Hamilton Custom House and the Thurgood Marshall U.S. Courthouse. Public buildings were often planned as part of larger complexes that grouped important civic buildings around landscaped public spaces.

Federal buildings embodied the Beaux Arts design principles of sophisticated proportioning and space planning, with monumental entrances leading to finely finished public lobbies and well-proportioned corridors that graciously welcomed citizens. The Beaux Arts style used white marble and limestone facades to faithfully recreate classical and renaissance models associated with the democracies of Greek and Rome.

From Designer to Patron: the Tarsney Act

Until 1893 the Supervising Architect’s office used in-house architects to design its buildings. But as the architectural profession grew, so did their protests and criticism about the way federal buildings were designed and built. Were the buildings designed by the Office of the Supervising Architect worthy of the country they were representing? Couldn’t private architects contribute to the vision and the legacy of the federal government?

In 1893 Missouri Congressman John Charles Tarsney introduced a bill that allowed the Supervising Architect to conduct design competitions among private architects for major structures.

The buildings produced under the Tarsney Act were a small fraction of the 400 federal buildings built over the 29 years the act was in effect (continuing controversy over patronage and cost overruns spurred its repeal in 1912).

The time following the repeal of the Tarsney Act marked a period of increasing standardization in federal buildings, although the office did continue to commission private architects such as Cass Gilbert, who designed federal buildings across the country. At the same time, the need for staff in the supervising architect’s office grew, while many young architects preferred to stay in private practice. So desperate was the need for young architects that beginning in the 1920s, the U.S. Civil Service produced radio programs and commercials aimed at attracting architects to the government.

Great Depression: Government Construction Accelerates

James T. Foley U.S. Courthouse, Albany, NY. Gander, Gander and Gander, Architect.

Photo Credit: Carol Highsmith.

More than forty percent of GSA’s historic building portfolio was built during the Great Depression. Congress understood that federal construction was a way to put people back to work, and repair the country’s infrastructure. Still other buildings, such as historic border inspection stations, came into being in response to changes in the American culture: Prohibition, immigration law, and the remarkable growth of car culture.

The Public Buildings Act of 1926 (Elliot-Fernald Act) authorized $50 million for the construction of federal buildings in Washington, DC. This included the development of the neoclassical Federal Triangle, the most ambitious federal construction campaign to date. The act also earmarked $150 million for construction projects outside the District of Columbia.

This expanded federal construction program, overseen by the Supervising Architect, maintained high standards for public building construction. Architects introduced the new esthetic of industrial design, which combined classical proportions with streamlined, Art Deco detailing. Integrated into many of these buildings were sculptural details, murals and statuary symbolizing or depicting important civic activities taking place inside.

A legacy of this era is the body of civic art commissioned under New Deal art programs. It is testament to the durability of these buildings that many of them remain in GSA’s inventory and continue to serve the functions for which they were built.

Things began to change in 1933, when the Office of the Supervising Architect was transferred to the Treasury’s newly created Procurement Division. In 1939, the Procurement Division and the Office of the Supervising Architect were removed from the Treasury Department and reassigned to the Public Buildings Administration. Oversight of federal design and construction became the responsibility of the newly founded Federal Works Administration in 1939.

World War II and the Post-war Shift

World War II saw a pause in federal architecture for civilians. This was the era of constructing temporary office buildings, housing, and hospitals to support the war effort. Twenty-nine office buildings were quickly erected in Washington, DC alone.

After the end of World War II, President Harry S. Truman created the U.S. General Services Administration in 1949. The new agency was created to bring order to the federal government. Dubbed “the most gigantic business on earth,” GSA consolidated the government’s immense building management and general procurement functions. GSA assumed the oversight of the design, construction, and preservation of most federal buildings.

During the 1950s, the role of the government went from designer to administrator of public buildings. Private firms were selected based on their credentials and public architecture began mimicking private office buildings. In 1956, the title of supervising architect was changed to assistant commissioner for design and construction. In the era of the Baby Boom, post-war federal construction accelerated. Between 1960 and 1976, GSA undertook more than 700 building projects.

Public and private architects embraced modernist design for its efficiency and use of new technology in engineering and building materials. As the government sought to house legions of federal workers and achieve the goals of standardization, direct purchase, mass production, and fiscal savings, were often stronger driving forces than architectural distinction. Quantity over quality frequently led to undistinguished, but functional, buildings.

Concerned that the caliber of federal construction was declining, President John F. Kennedy, in 1962, convened the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space, which proposed the Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture. These principles called for design that reflected “the dignity, enterprise, vigor and stability of the American national government, [placing] emphasis…on the choice of designs that embody the finest contemporary American architectural thought,” a philosophy that continues to guide the design of public buildings today.

Federal Modernism

Strom Thurmond Federal Building & U.S. Courthouse, Columbia, SC. A sophisticated example of the Brutalist style. Marcel Breuer, Architect.

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith.

Not every federal building of that era was a big bland box. When GSA built modern at its best, it produced strikingly contemporary designs by modern masters:

Marcel Breuer’s sweeping Washington, DC headquarters for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, named for the first African American member of the Cabinet;

Mies van der Rohe’s sleek Federal Center in Chicago, Illinois, and

Victor Lundy’s boldly sculptural U.S. Tax Court Building in Washington, DC.

The majority of buildings GSA constructed during the federal modernism period of the 1960s and early 1970s reflect typical office design: functional, efficient, but not necessarily distinguished. The philosophy of the Modern movement, coupled with the pace of changing technology, gave rise to a new commercial standard, which was reflected in many public buildings of the period. Buildings had an anticipated life span of 20-30 years, which is the typical lifecycle of modern mechanical systems and also the standard period used for calculating return on investment. Unlike their predecessors, these buildings were not constructed to last centuries.

GSA actively evaluates these buildings’ eligibility for listing in the National Register of Historic Places as they reach the 50-year age threshold.

Design Excellence Program

The Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture continue to exert influence: they provided the structure for a conversation around public architecture that led to the establishment of GSA’s Design Excellence program in 1992. The program embodies the philosophy that federal buildings should be symbolic of what government is about, not just places where public business is conducted.

Today, as the principal builder for the civilian federal government, GSA strives to shape this legacy and the way people regard their government through its public buildings. The program encourages design that embodies the finest contemporary American architectural thought, reflects regional architectural traditions, and provides high-quality, cost-effective, and lasting public buildings for the enjoyment of future generations.

The program has led to powerful collaborations with top-tier architects who might never before have considered designing a federal building, engaged in peer reviews of new building designs, and cross-disciplinary conversations about what makes a federal building great.

Into the 21st Century: Restoration and Recovery

50 United Nations Plaza Federal Building, San Francisco, CA. The seven story steel frame and masonry Beaux-Arts Neo-Classical style building underwent a full modernization and renovation funded AARA monies. Arthur Brown, Jr., Architect.

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith.

Continuing into the 21st century, GSA and the federal government have responded to big changes: changes in the way citizens relate to their government. Changes to the environment. And changes in the economy.

Most recently, the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (ARRA), an economic stimulus package, was signed into law by President Barack Obama. Part of this program included investing an unprecedented $1.665 billion for modernization projects at 150 GSA historic buildings.

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration