U.S. Tax Court Building in Washington DC, designed by master architect and artist Victor Lundy

The decades of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s, a period that sparked great innovation in the design and engineering fields, were accompanied by extensive federal government growth. It was during this time that GSA’s construction budget increased dramatically. Between 1960 and 1976 alone, GSA undertook more than 700 building projects across the United States. These included office buildings, courthouses, post offices, and border inspection stations, many executed in modern styles.

Encompassing the presidencies of Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon, this era is popularly defined as the period of federal modernism. Historic events such as landmark civil rights legislation, the War on Poverty, and the Vietnam War influenced government policy and planning. Meanwhile, many architects embraced a sharp-edged style that shunned ornamentation. (Think of almost any tall building seen in the recent television show Mad Men, or Washington D.C.’s Hirshhorn Museum.) Masters of federal modernism include:

Architect: Marcel Breuer

Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, Washington, DC

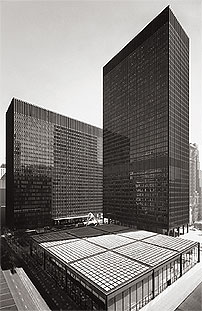

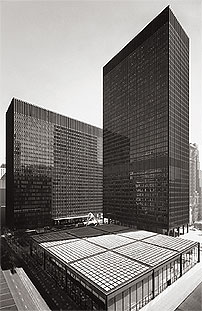

Architect: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe

Chicago Federal Center, Chicago, IL

Architect: Walter Gropius

John F. Kennedy Federal Building

One of the most dramatic modern examples in the GSA inventory is the U.S. Tax Court Building in Washington D.C., designed by master architect and artist Victor Lundy. At the time of its designation in 2008, Lundy’s Tax Court was the youngest of GSA’s building to receive such distinction from the National Register of Historic Places. To learn more about Lundy’s design and his inspirations, you can view this 48-minute documentary film.

The approach to historic building designation is standard but broad enough to accommodate all eras of design. As with other building styles, modernism’s popularity has waxed and waned. Its disdain for ornamentation and fondness for massive forms have sometimes been seen as an expression of efficiency and power—and at other times, as sterile and inhuman. As more and more buildings in this style reach the 50-year mark, making them eligible for listing in the National Register and subject to evaluation by GSA, the conversation has grown more complex and increasingly informed.

To learn more about the federal buildings constructed during this time, and why and when they might be considered historically significant, review the following downloadable guides and web pages:

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration