Architecture, particularly public architecture, develops in response to a government and its people. Laws, technological advances, symbolic needs, functional requirements, and social aesthetics also exert strong influence. To understand the impact these influences had on architecture provides insights into how and why it changes over time.

The timeline below highlights some of the more important events in the evolution of American architecture as it developed alongside the nation.

1789-1851

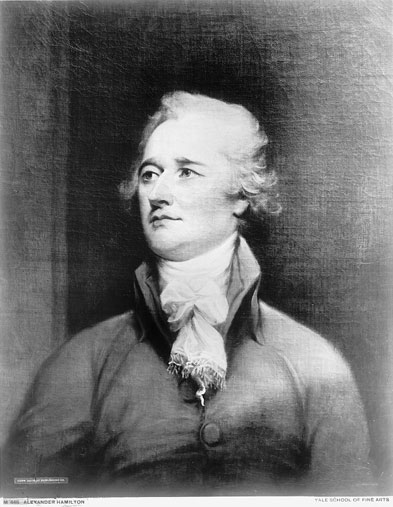

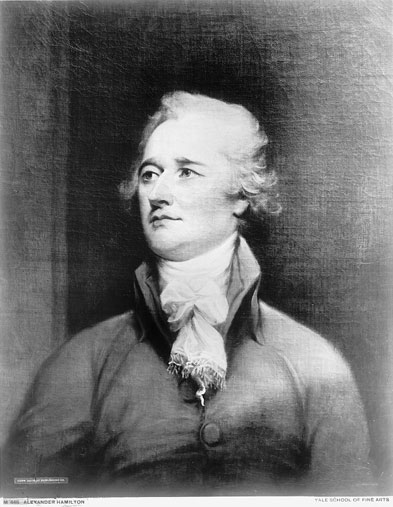

Alexander Hamilton was the first Secretary of the Treasury (1789-1795)

Photo Credit: US Treasury Department

During the early decades of the new republic, the U.S. Treasury Department manages construction appropriations, but local federal officials oversee the design and construction of important government buildings including early custom houses. Prominent private architects are engaged. Buildings are often monumental, reflecting the power and authority of the government and distinguishing federal structures from those built for the private sector.

1807

Congress passes the first act to authorize the construction of a custom house in New Orleans, Louisiana. $20,000 is appropriated. Noted architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe, often referred to today as “the Father of American Architecture” is selected to design the building, which he did from a remote distance.

1809

Construction completed on Latrobe’s New Orleans Custom House. The building is one of the first in the city to use locally sourced red bricks, white columns and trim, and green blinds. The materials and colors soon become typical characteristics of buildings in New Orleans. Within a decade, the building was ready for replacement due to its hasty construction and poor foundation.

1817

Funds of $50,000 appropriated to build custom houses and public warehouses for federal use; these structures are to be built in the principal district of each state, as deemed necessary by the secretary of the Treasury (at that time William H. Crawford), for the safe and convenient collection of revenue.

1832

Congress authorizes the construction of a custom house in New Bedford, Massachusetts. The initial appropriation is $15,000, but the funds are insufficient to meet new U.S. Treasury Department requirements for fireproof construction. The final cost is more than double the original appropriation.

1833

Erected between 1834-36, Robert Mills designed this Greek Revival Custom House in New Bedford, MA.

Robert Mills designs the New Bedford Custom House, as well as three others in New England, in one of the government’s earliest examples of standardized construction. These standardized buildings form a pattern of design and supervision for the federal building program in later years.

1836

Robert Mills, architect of many federal buildings in 19th-century America.

President Andrew Jackson appoints Robert Mills architect of public buildings in Washington, D.C. The position will later evolve as the supervising architect of the Department of the U.S. Treasury.

1836 - 1869

Construction begins on the U.S. Treasury building. Its construction spans 33 years, and today it is the oldest departmental building in Washington DC. A magnificent example of Greek Revival style, the building has a great impact on the design of other government buildings.

First to be built are the east and center wings, completed in 1842. They are designed by Robert Mills. Additional wings, south and west, are added in 1860 and 1864 respectively. Thomas Ustick Walter is the designer, with input from Ammi B. Young and Isaiah Rogers. The final addition, the north wing, is completed in 1869; Alfred B. Mullett serves as architect.

1852

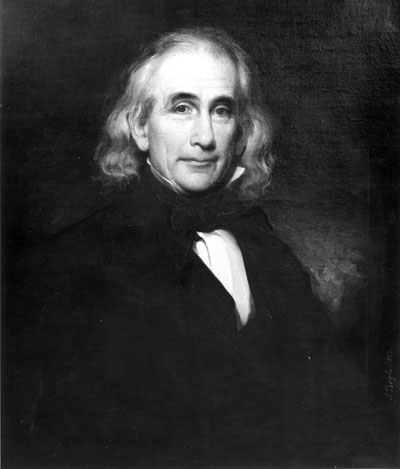

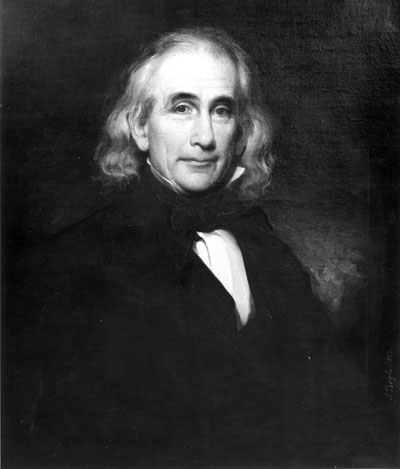

Portrait of Ammi B. Young, first supervising architect of the U.S. Treasury Department.

The Bureau of Construction is established by the Secretary of the Treasury to coordinate and oversee federal design and construction projects.

Ammi B. Young becomes the first architect to be called the “Supervising Architect.” Over time, the bureau becomes known as the Office of the Supervising Architect. Young heads the office until 1861, when the Civil War brings building projects to a halt.

1853

Treasury Secretary James Guthrie reports on the federally owned building inventory to Congress: twenty-four buildings, nine of which are purchased from private parties. Fifteen additional buildings have their funding appropriated and are awaiting construction.

1853 - 1858

Owen B. Pickett U.S. Custom House, Norfolk, VA

Owen B. Pickett U.S. Custom House, Norfolk, Virginia, is constructed. It replaces the original custom house built in 1819. Ammi B. Young, supervising architect of the Treasury, designs the building in classical Roman Temple architectural style. A prominent parcel of land, the site for the new custom house, is purchased for $13,500.

1855 - 1858

Richmond VA Customs House standing among ruins.

Image from Library of Congress’ Civil War glass negative collection.

, Richmond, Virginia, is built; it remains the oldest courthouse in GSA’s inventory. Ammi B. Young, supervising architect of the Treasury, designs the impressive Italianate structure. The courthouse is one of two buildings in the historic section of Richmond to survive the fires set by the evacuating Confederate Army in the last days of the Civil War.

1864

Congress passes an act approving the appointment of a supervising architect in the construction branch of the Treasury Department; a subsequent act funds the position through 1872.

1871

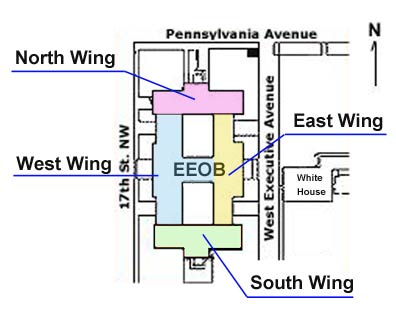

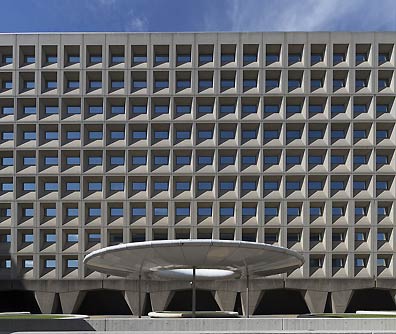

Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building, Washington, DC

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith

Alfred B. Mullett is commissioned to design the State, War, and Navy Department Building in Washington, DC. (now the Dwight D. Eisenhower Executive Office Building).

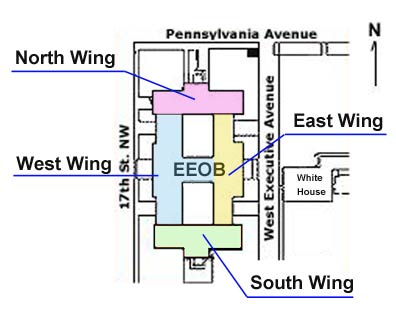

Built in four stages, the building replaces two existing executive office buildings that stood west of the White House. The south wing (1871-1875) houses the State Department. The east wing (1872-1879) houses the Navy Department. The north (1879-1882), west and center wings (1884-1888) house the War Department.

Illustration showing the location of each wing of the Eisenhower Executive Office Building

1873

The Old Post Office, Washington, DC, designed by Willoughby J. Edbrooke, supervising architect of the U.S. Treasury Department, in the Romanesque Revival style.

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith

The financial panic of 1873 leads to a six-year depression in North America and Europe. Many factors converge to trigger the panic: over-expansion of the American railroad system, a plummet in the price of silver, and a run on Wall Street that closes the NY Stock Exchange for 10 days.

The depression affects the federal building program. Second Empire style buildings suddenly seem overly grand and expensive in an era of hard economic times. The less decorative Romanesque Revival style, characterized by massive, rough-textured stone walls, rounded arches, and square towers, becomes popular for federal buildings constructed in the 1880s.

1893

Tarsney Act passes in Congress. It allows the Treasury Department to acquire the services of architects working in private practice. For the first time since the country’s founding, private architects can compete for major federal design assignments.

Ultimately over 30 buildings are built during the life of the Tarsney Act. One of the most iconic buildings constructed under the Tarsney Act is the Alexander Hamilton U.S. Custom House in New York City by architect Cass Gilbert.

Palace of Mechanic Arts and lagoon at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, IL.

Photo Credit: Frances Benjamin Johnston/Library of Congress

The success of the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, in 1893, cements acceptance of Neoclassicism in both architectural and public circles.

Millions of visitors are dazzled by fourteen “great buildings” situated around a huge reflective pool. Because the buildings are “lathered with plaster of Paris, and painted a chalky white, [they were given] the moniker ‘White City.’” The grand scale, symmetry, elaborate ornamentation, and classical details of these buildings soon influence the design of federal buildings. The first large-scale manifestation of the City Beautiful movement, the fair’s impact will transform public architecture for the next fifty years.

1897

James Knox Taylor becomes supervising architect in October. He is the first architect to be chosen under the Civil Service Law. Projects under his tenure adhere to the classical style: monumental entrances, grand public lobbies, facades of white limestone or marble. Taylor holds the office until 1912, five years longer than anyone who came before him. During this time, the Office of the Supervising Architect will grow from a staff of 150 to 251. The number of completed buildings during this time increases by 133 percent.

1906

American Antiquities Act passes, enabling the president to declare landmarks, structures, and other objects of historic or scientific interest as national monuments. It is the first law to establish that archeological sites on public lands are important public resources.

1912

Tarsney Act repealed under claims of excessive costs associated with holding design competitions for private architectural firms.

1913

Congress creates the Public Buildings Commission to draft recommendations on standardizing and streamlining the building management process.

1915

James A. Wetmore becomes acting supervising architect of the Treasury, a position he would hold for almost twenty years. Though a lawyer by trade, Wetmore’s management abilities and knowledge of the legislative processes were such that the Treasury Department did not appoint a permanent replacement.

1926

Great Plaza, Federal Triangle. Construction of Great Plaza with Department of the Post Office at 13th and D St. (ca. 1920-ca. 1950)

Photo Credit: Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Theodor Horydczak Collection, [reproduction number, e.g., LC-H824-0224]

Public Buildings Act of 1926 (Elliot-Fernald Act) passes; authorizing $50 million for the construction of federal buildings in Washington, DC. This includes the development of the neoclassical Federal Triangle, the most ambitious federal construction campaign to date. The act also earmarks $150 million for construction projects outside the District of Columbia.

1929

The stock market crashes and the Great Depression begins. With many Americans out of work, the public buildings program is looked to as a potential source of employment.

1930

The Keyes-Elliott Bill, an amendment to the Public Buildings Act of 1926, passes. The bill provides the secretary of the Treasury increased authority for entering into service contracts with private architects. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) begins a concerted lobbying effort for the Office of the Supervising Architect to reorganize as a management organization and cease its federal building design responsibilities. The AIA’s campaign is largely unsuccessful, as the government retains design responsibility for the smaller projects, awarding only larger commissions to private firms.

Late 1920s-

Early 1930s

The Joel Solomon Federal Building and U.S. Courthouse, Chattanooga, Tennessee

Photo credit: Carol M. Highsmith

Private sector begins to embrace modern architectural ideals and new building technologies. Examples include Rockefeller Center (Associated Architects) in New York City and the Philadelphia Savings Fund Society building (Howe and Lescaze) in Philadelphia.

During the 1930s, the government embarks on a prolific construction program, and federal buildings throughout the country are planned and executed. Many buildings continue to reflect traditional styles, though they increasingly bear the influences of the early modern movement. Used primarily for government architecture, a new architectural style emerges that effectively straddles classicism and modernism. Simplified neoclassical forms are paired with the stylized designs of the Art Deco style. This new public building style is today alternately known as Stripped Classicism, Starved Classicism—or PWA Modern in recognition of the Public Works Administration that oversaw many such designs.

1931

Cass Gilbert, American Architect

Photo Credit: Harris & Ewing

Cass Gilbert is commissioned to design the U.S. Courthouse at Foley Square in New York City (now the Thurgood Marshall U.S. Courthouse). It is among the first federal skyscrapers constructed in America. Construction begins in July 1932 and lasts three and a half years. Gilbert dies during the building’s construction; his son, Cass Gilbert Jr., takes over supervision of the building’s completion.

1933

The Procurement Division is created within the U.S. Treasury Department, and the Office of the Supervising Architect is transferred and renamed the Public Works Branch. The AIA continues to lobby for private architects to be awarded more federal design contracts.

1935

Congress passes the Historic Sites Act, which “declares that it is a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings, and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States.”

The act creates programs for the research, inventory, and organization of historic sites.

1939

The Public Works Branch is removed from the U.S. Treasury Department and becomes part of the Public Buildings Administration of the Federal Works Agency. The end of the Office of the Supervising Architect of the Treasury marks the beginning of a new era in federal building design and construction.

1938 – 1943

Congress passes the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signs it into law. President Roosevelt then issues Executive Order 7034, establishing the Works Progress Administration (WPA). The WPA seeks to provide employment to the millions of unemployed Americans.

Among many undertakings, the WPA provides funding for myriad public building projects, including courthouses, airports, and federal office buildings. These are partially funded by state and local governments, which provide 10-30% of the funding.

1947

With the demand for office space critical following World War II, the Hoover Commission identifies the need for a centralized support service for the federal government, “the most gigantic business on earth,” and recommends the creation of an Office of General Services.

1949

The Seal of the General Services Administration (GSA)

Federal Property and Administrative Services Act passes. The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) is created, which includes the Public Buildings Service, the division responsible for the design, construction, and management of federal buildings.

The act authorizes the employment of private architects for public building projects once again.

1951 - 1952

Construction concludes on two highly influential Modernist works: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe’s Lakeshore Apartments in Chicago and Skidmore, Owings & Merrill’s Lever House in New York City. Both architectural firms later design buildings for GSA.

1959

Public Buildings Act of 1959 passes. GSA assumes responsibility for federal construction, ending unsuccessful lease-purchase efforts.

1961 - 1962

President John F. Kennedy creates Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space. “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture” issued, encouraging the “finest contemporary American architectural thought” for designs of new federal buildings. It also advocates the inclusion of fine arts, preferably by living American artists, where appropriate.

Daniel P. Moynihan, senator from New York, is given credit for the ideas in the report, which become a “touchstone” for discussion of federal buildings.

1962

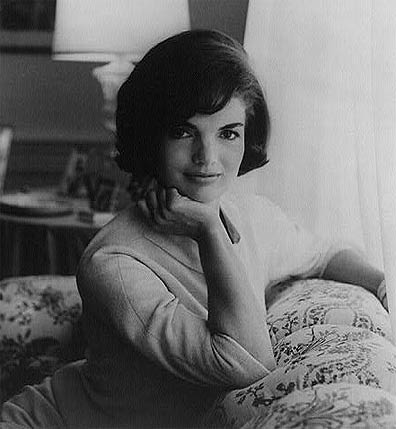

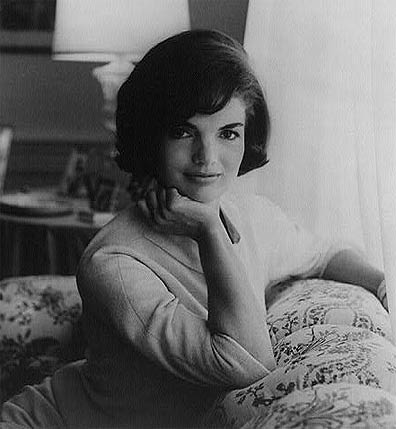

First official White House photograph of First Lady, Jacqueline Kennedy, 1961.

Photo Credit: Mark Shaw

First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy spends the first years of her husband’s presidency restoring splendor and history to the White House. On February 14, 1962, “A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy” airs on CBS. An estimated 56 million Americans tune in to see her talk about White House history and the need for historic preservation.

Later that same year, Mrs. Kennedy begins to bring her position and considerable powers of persuasion to bear to save Lafayette Square’s row houses from the wrecker’s ball. She writes to GSA Administrator Bernard L. Boutin, asking him to “[preserve] the 19th Century feeling of Lafayette Square” and that she “so strongly feels that the White House should give the example in preserving our nation’s past.”

Metropolis

Glass mosaic by Seymour Fogel. 1967

Located in the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building/Court of International Trade, New York, NY

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith

The integration of art in public buildings is recognized by the Kennedy administration, as a priority, with a focus on sculpture and murals.

1963

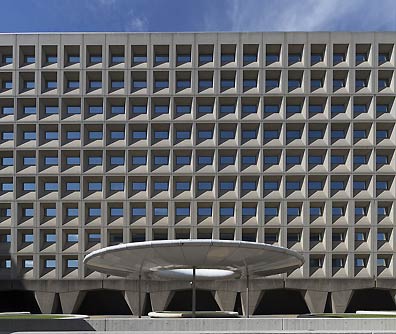

Robert C. Weaver Federal Building, Washington, DC. Marcel Breuer, Architect.

Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith

Construction begins on the headquarters of the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in Washington, DC (later named the Robert C. Weaver Federal Building). During this period, the building’s architect, Marcel Breuer, brings European modernism to America, creating the foundation for the U.S. modern architecture movement.

1964

Construction underway on the Federal Center, Chicago, IL. View is to the northwest.

Photo dated May 28, 1964.

Construction completed on early phase of the Federal Center in Chicago; it eventually consists of three buildings: John C. Kluczynski Federal Building; Loop Station Post Office; and Everett M. Dirksen U.S. Courthouse.

The simple, well-proportioned steel and glass design epitomizes the minimalist architectural approach favored by its architect, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, considered one of the greatest architects of the 20th century.

1964

Lady Bird Johnson plants pansies as Secretary Stewart Udall and others look on.

Photo Credit: LBJ Library photo by Robert Knudsen

President Lyndon B. Johnson initiates the Program for Beautification of Federal Buildings with the objective of improving the appearance of federal buildings and their grounds.

President Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson are instrumental in passing the Highway Beautification Act in 1965. It places restrictions on billboard advertising and fosters aesthetic consideration of landscapes along America’s highway system.

1966

Congress passes the National Historic Preservation Act, declaring that “the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon its historic heritage.” The act creates the National Register of Historic Places, state historic preservation offices, and federal preservation offices, and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. A formal framework that requires the federal government to take into account the effect of its undertakings on cultural resources is established.

1968

Architectural Barriers Act of 1968 passes. Requires federally funded facilities to be accessible to people with disabilities. This is one of the first pieces of federal legislation to address this issue. GSA is responsible for reporting agency activities in support of this act.

1969

U.S. Tax Court Building, Washington, DC

The building is considered one of the most sophisticated and successful examples of Modernism in DC.

Construction begins on the U.S. Tax Court in Washington, DC. The building is a direct result of the “Guiding Principles for Federal Architecture” issued by the Ad Hoc Committee on Federal Office Space at the request of President John F. Kennedy in 1962.

The Modernist design by master architect Victor Lundy is hailed as an example of “genuine classicism.” Watch the Center for Historic Buildings’ documentary: Victor Lundy: Sculptor of Space.

National Environmental Policy Act passes. Energy conservation becomes a priority for federal buildings.

1972

Grand State of Maine

Bronze sculpture by Nina Katchadourian

Land Port of Entry, Van Buren, ME

Commissioned through the Art in Architecture Program

GSA establishes the Art in Architecture program, recognizing the importance of public art in federal buildings.

The program commissions American artists to create publicly scaled and permanently installed works of art for federal buildings across the nation. GSA allocates one-half of one percent of the estimated construction costs of new buildings and the modernization of existing buildings to commission artists.

1974

Housing and Community Development Act of 1974 passes. Creates “Section 8” rental housing for low-income tenants. The act also establishes the National Institute of Building Sciences, with the mission to “serve as an interface between government and the private sector.” The institute’s public interest mission is to serve the nation by supporting advances in building science and technology to improve the built environment.

1975

The Norris Cotton Federal Building in Manchester, NH, is a prototype energy-efficiency building with solar panels and several distinct mechanical and lighting systems.

Two federal buildings incorporating energy conservation technology are constructed:

- U.S. Courthouse and Federal Building in Williamsport, PA; Architect: Burns & Loewe

- Norris Cotton Federal Building in Manchester, NH; Architect: Isaak & Isaak.

1976

Public Buildings Cooperative Use Act passes. It encourages the location of commercial, cultural, educational and recreational facilities and activities within public buildings.

Commercial and service-related uses are allowed in federal buildings in an effort to revitalize downtowns.

1990

GSA Design Awards established, recognizing high-quality federal design. The Design Awards celebrate the accomplishments of architects, engineers, landscape architects, urban planners, interior designers, artists, conservationists, and preservationists who create and safeguard the nation’s landmarks.

Photo of President George H.W. Bush signing into law the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 on the South Lawn of the White House. L to R, sitting: Evan Kemp, Chairman, Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, Justin Dart, Chairman, President’s Committee on Employment of People with Disabilities. L to R, standing: Rev. Harold Wilke and Swift Parrino, Chairperson, National Council on Disability, 07/26/1990.

Americans with Disabilities Act passes. President George H.W. Bush holds the largest signing ceremony in history on the south lawn of the White House. This landmark civil rights legislation not only makes discrimination against people with disabilities illegal, but also establishes the Standards for Accessible Design (amended again in 2010).

These standards and technical specifications provide a framework for making buildings accessible to people with disabilities. They also include detailed guidance for making historic buildings accessible.

1992

The Energy Policy Act of 1992 passes. It calls for the creation of new building energy efficiency standards, and then requires new federal buildings to comply with them. New construction of private homes and other residential housing subject to mortgages insured under the National Housing Act must also comply with the standards.

1994

GSA’s Design Excellence program created. Select federal buildings are designed by masters of contemporary architecture.

1999

GSA’s First Impressions initiative established to rehabilitate the entrances and lobbies of federal buildings, improving the entrance experience for both visitors and employees.

2003

Conceived by Cooper Hewitt, the National Design Awards are launched to recognize significant and lasting achievement in American design.

2009

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, an economic stimulus package, is signed into law by President Barack Obama, investing an unprecedented $1.665 billion for modernization projects at 150 GSA historic buildings.

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration