A “roof over our heads” is an essential part of a building envelope, protecting occupants and building structures and systems from the elements. While the value of a durable, leak-resistant roof is clear, traditional roofs can have many negative impacts, including contributing to the urban heat island effect and to stormwater runoff. Roof space, an often wasted resource, has the potential to:

- Help save or generate energy

- Slow stormwater runoff rates

- Bolster biodiversity

- Enhance building aesthetics and tenant amenities

There are an increasing number of options to take full advantage of the environment on top of your building, including planted roofs, cool roofs, and solar roofs.

Planted roofs

Planted roofs — also known as vegetated roofs or eco-roofs — use plants as a technology to help bring the natural cooling, water-treatment and air filtration properties of vegetated landscapes to the urban environment. These systems consist of vegetation (plants), growing medium (soil) and a waterproofing membrane, overlying a traditional roof. There are two primary types of planted roofs: extensive and intensive. Extensive planted roofs consist of small succulent plants, while intensive planted roofs have greater plant diversity, including native vegetation, bushes, or trees.

According to a GSA report [PDF - 9 MB], building owners can achieve lifetime cost savings of about $4.15 per square foot by installing a planted roof instead of a conventional roof. This report includes a literature review of 200 research studies, in-depth analysis of planted roof benefits, original cost-benefit analysis, discussion of challenges and best practices, and assessment of further research needs. The cost-benefit analysis finds that planted roofs on commercial and public buildings provide a payback, based on 50 year average annual savings, of about 6.2 years nationally, an internal rate of return of 5.2%, and an ROI of 224%, based on a net present value of $2.7 per square foot. The primary costs are related to installation and maintenance and the primary economic benefits are lower energy costs, less frequent roof replacement due to greater durability, reduced stormwater management costs, and creation of job opportunities.

Planted roof components

Planted roof

Extensive planted roofs

Planted roof at the Department of the Interior

Extensive planted roofs feature mostly small succulent plants, such as sedums, selected for their ability to thrive in harsh rooftop conditions which usually include high sunlight and heat and intermittent water. These roofs do not require deep layers of soil or much ongoing maintenance, making them lighter, less expensive and often a practical option. They may or may not be open to building occupants or the public. Two options are built-in-place and modular planted roofs:

- Built-in-place planted roofs are built in one continuous unit on the rooftop where it is installed. Built-in-place roofs can consistently provide all the benefits of a planted roof, e.g, slowing stormwater runoff at a lower cost since they constitute one cohesive unit without gaps.

- Modular planted roofs consist of a series of growing medium and vegetation trays which are delivered to a building and installed. Modular roofs, by contrast, can provide conveniences including ease of installation and ability for each unit to be removed and replaced individually, which may be useful for future maintenance.

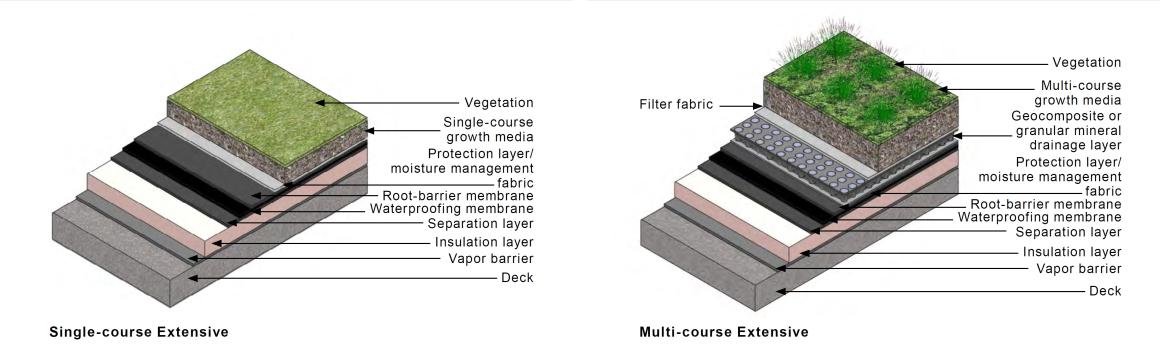

Extensive planted roofs can be single-course or multi-course in application.

Extensive roof types| Roof type | Single-course extensive | Multi-course extensive |

|---|

| Thickness | 3-4 inches | 4-6 inches |

|---|

| Drainage layer | No discrete drainage layer | Based on the growth media thickness, plants selected, local climactic conditions, and rooftop hydrologic conditions; synthetic geocomposite are typical nationally |

|---|

| Vegetation layer | Sedum or other succulents | Sedum or other succulents; potential for other plants as thickness increases or with permanent irrigation |

|---|

| Media type | Coarse media over moisture-management layer | Finer-grained growth media over discrete drainage layer |

|---|

| Irrigation | Typically none | Typically necessary in the first year to establish growth in Mid-Atlantic |

|---|

| Prevalence | Common internationally; area with sufficient precipitation is necessary | Nationally the most common planted roof type |

|---|

Source: The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings [PDF - 9 MB]

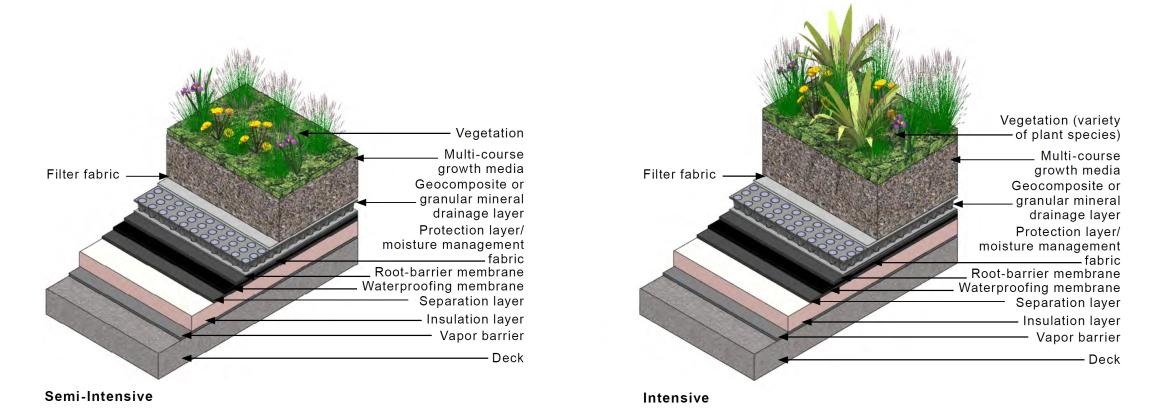

Intensive planted roofs

Planted roof at the U.S. Tax Court Plaza in Washington, DC

Intensive planted roofs feature greater levels of plant diversity — which includes native vegetation, bushes or even trees — than extensive planted roofs. As a result, intensive planted roofs can provide greater intangible benefits, including enhanced community spaces and support of urban biodiversity through the creation of a more diverse habitat. Intensive planted roofs, which can be semi-intensive or intensive, may require additional resources, however, for a thicker layer of soil, enhanced structural support, more frequent irrigation and other maintenance.

Intensive roof types| Roof type | Semi-intensive | Intensive |

|---|

| Thickness | 6-12 inches | Over 12 inches |

|---|

| Drainage layer | Discrete drainage layer | Discrete drainage layer |

|---|

| Vegetation layer | In the Mid-Atlantic and with irrigation, supports a variety of plants — meadow species, ornamental varieties, woody perennials, and turf grass | Supports plant communities similar to ground-level landscapes depending on thickness and exposure |

|---|

| Media type | Multi-course over discrete drainage layer | Intensive growth media layer over discrete drainage layer. Topping media may be used including higher organic content, greater density, greater water holding capacity, and lower permeability |

|---|

| Irrigation | Required if turf grass is used | Required |

|---|

| Prevalence | Common; provides more variety in vegetation | Less common than the other types; structural capacity and maintenance are limiting factors |

|---|

Source: The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings [PDF - 9 MB]

High reflectance roofs

High reflectance roofs, also known as high albedo, white, or cool roofs, are made of light-colored materials that reflect a majority of sunlight away from the building as compared to traditional black roofs that absorb heat.

Benefits

- Reduction in the urban heat island effect by reflecting sunlight and heat away from the building

- Reduction in the energy needed to cool buildings in the summer

- In very warm or desert climates, white roofs can outperform planted roofs in reducing energy use and heat islands. Costs and benefits of each should be evaluated project by project.

Challenges

- Reflected sunlight can be absorbed by adjacent surfaces, thereby unintentionally warming them

- Similar stormwater runoff issues as traditional black roofs

- Performance decreases over time as the roof weathers and accumulates dirt and other particles, causing the roof to absorb more solar energy

- Regular upkeep is required to maintain desired performance

Solar photovoltaic

Solar panels at EPA’s Region 8 Office in Denver, Colorado

Photovoltaic or PV roofs convert light from the sun into usable direct current or DC. Rooftop applications generally feature two types of panels:

- Amorphous silicon panels: These panels consist of a thin layer of silicon deposited on a backing. This thin film can come in rigid panels or as a flexible lightweight panel that can be adhered to a membrane and fastened directly to the roof membrane.

- Crystalline silicon panels: These panels are more common, generate more wattage, and are more durable than amorphous or thin-film panels. They typically are made by laminating the cells between tempered glass and plastic and framing it with aluminum. Thin panels require a larger surface area compared to a crystalline panel, due to their reduced efficiency. But in low-light conditions, thin-panel performance is better.

See NREL’s Solar Page for more information.

The voltage produced by a solar panel falls as its temperature increases, so solar panels on a cooler roof will produce more power than those on a hotter one. This means that solar panels can operate more efficiently on a planted roof than they do on a conventional roof, which heats up more in the sun. The electrical output of solar panels on planted roofs in Berlin, Germany, and Portland, Oregon, has been observed to increase by up to 6%.1

When designing a new solar system, also consider whether solar hot water heating is appropriate. The Energy Independence and Security Act or 2007 requires that no less than 30 percent of the hot water demand for each new Federal building or major renovation must be met through solar hot water, if lifecycle cost-effective.

Stormwater management

Most urban and suburban areas contain large amounts of paved or constructed surfaces which prevent stormwater from being absorbed back into the ground. The resulting excess runoff can erode river banks, cause flooding, and overload water treatment systems resulting in damage to water quality by sweeping urban pollutants into nearby water bodies. Non-permeable roofing systems can be a significant contributor to these pollutants and are a critical component to sustainable stormwater management. See EPA’s Low Impact Development page for more information.

Planted roofs can form a key part of a site-level stormwater management plan, reducing peak flow rates by up to 65% and increasing the amount of time it takes for water to flow from a site into the sewer by up to three hours, depending on the size of the roof and the distance the water has to travel. Planted roofs reduce runoff rates after both large and small storms. Installing a planted roof at least 3 inches thick on a large enough area can reduce the frequency of sewer overflows during the summer season.1

Some studies suggest that planted roofs improve the quality of rainwater runoff from roofs, as plants take up potential contaminants from the soil and store them in their tissues. Other studies have found that planted roofs actually contribute nutrients to rainwater runoff during the initial establishment period, which can negatively affect surface water.2 The definition of which chemicals in stormwater runoff are considered pollutants depends on the characteristics of the receiving waters into which the runoff will flow. If they are low on a particular nutrient, its presence in runoff may be seen as beneficial. The amount of nutrients in runoff from a planted roof depends on the content of the rain, whether fertilizer is used on the roof, and the materials used to produce the growth medium, particularly the compost.

Benefits summary

- Energy: Planted roofs reduce building energy use by cooling roofs and providing shading, thermal mass and insulation.

- Stormwater management: Most urban and suburban areas contain large amounts of paved or constructed surfaces, which prevent stormwater from being absorbed into the ground. The resulting excess runoff damages water quality by sweeping pollutants into water bodies. Planted roofs can reduce the flow of stormwater from a roof by up to 65% and delay the flow rate by up to three hours, thus reducing pollutants being swept into water bodies.

- Biodiversity and habitat: Planted roofs replace urban habitat for plants and animals, like birds and insects, thereby increasing biodiversity. Specific goals like increasing nesting and foraging for pollinator species like bees can be incorporated in a project. See the Presidential Memorandum on pollinators and the National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey bees and Other Pollinators.

- Urban heat islands: Cities are generally warmer than other areas, as concrete and asphalt absorb solar radiation, leading to increased energy consumption, heat-related illness and death, and air pollution. Planted roofs can help mitigate these effects. See A Temperature and Seasonal Energy Analysis of Green, White, and Black Roofs [PDF - 1 MB] for more information.

- Roof longevity: Planted roofs are expected to last twice as long as conventional roofs

- Aesthetics: Planted roofs can add beauty and value to buildings.

Installation

Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives Planted Roof Installation

Materials and layers

Waterproof membrane

A waterproof membrane is designed to protect the building components from the weather, over which the vegetative roof system is installed. Membranes are required for all roofs types. For this reason, the membrane should be removed from any cost-analysis comparisons when determining between different types of roof to install.

We recommend that design teams at least utilize an inverted roofing membrane assembly or IRMA.

Leak detection system

Leak detection systems help identify problem areas where water surpasses the membrane and could cause roof damage if left unattended. The electronic leak detection method enables the detection and location of any leak, even pin-hole-sized defects, but requires the installation of a fine grid of metal wire within the planted roof and waterproofing layers.

Drainage layer

Planted roof drainage layers carry the excess stormwater runoff to the roof drains, and eventually off the roof. A properly designed planted roof will not have water sitting on top of it — any stored water will reside in the growing medium and vegetation.

There are three main types of drainage layers used on planted roofs: simple geocomposite drain layers, reservoir sheets, and granular mineral medium.

- Granular medium is the best at slowing and delaying runoff.

- Reservoir sheets are designed to capture rainwater in indentations in their surface.

- Geocomposites, or multi-layered materials made from a combination of synthetic polymers, are adapted for planted roofs and designed to allow water to flow easily through the material, draining excess water away from a roof.

The type of drainage layer and the type of separation or moisture retention fabrics used in a roof will influence the roof’s performance.

Root-resistant layer

A membrane designed to provide protection to the underlying waterproofing membrane from root penetration and provide protection from microorganisms in the growth medium. Failure to use a root-barrier can cause structural damage to the waterproof membrane, and therefore can subsequently lead to demolition of the planted roof and the underlying waterproofing.

Growing medium

National Foreign Affairs Training Center (NFATC) Planted Roof Installation

Germany’s FLL Guidelines on planted roofs suggest the medium used on a planted roof generally retains from 30% to 60% of water by volume when totally saturated with water. The size of growth medium particles, the types of materials used and the depth of the medium all affect the amount of moisture the medium can retain.

- Size: Smaller particles have a higher surface area-to-mass ratio and smaller pores, both of which enhances the medium’s water retention capacity and capillarity, or its ability to absorb water through the capillary action that draws water into a particle.

- Type: As the proportion of organic matter in growth medium increases, so does its water retention capacity. However, too much organic material in a medium can cause it to shrink as the material decomposes. If the organic material contains high levels of nutrient salts, or various phosphorus and nitrogen compounds that have a fertilizing effect, it can even decrease the quality of runoff from the roof.

- Depth: The thicker the growth medium the more water the roof can absorb, at least up to a point. In general, a thicker roof can be expected to retain more water from an individual storm. A 4-inch roof can typically retain 1 to 1.5 inches of rain. This means that in the summer, when most storms produce less than 1 inch of precipitation, 90% of storms are largely retained. However, benefits do not depend exclusively on depth, and thinner extensive planted roofs yield the greatest benefit-to-cost ratio.

Vegetation

Vegetation should be chosen based planted roof type for example, extensive or intensive and on the local climate.

Planted roof type: Intensive planted roofs can include plantings with deep woody roots such as bushes and trees, while extensive planted roofs generally have plantings of low-growing, hardy sedums. Note that grass is generally not used on planted roofs.

Climate: Always give preference to native plant species when choosing vegetation. Sedums can also survive harsher environments of higher elevations and perform as a fire-break on the roof.

See extensive and intensive planted roofs for more information.

Potential vegetation for extensive and semi-intensive planted roofs1

3” Extensive succulents

Sedum floriferum cultivars

Sedum reflexum — rupestre cultivars

6” Semi-intensive perennials supplemented with sedum

Achillea millefolium cultivars

Echinacea purpurea cultivars

6” Semi-intensive grasses supplemented with sedum

Pennisetum alopecuroides cultivars

Schizachyrium scoparium cultivars

Roof load

The dead load of a planted roof system is influenced by a number of factors, including contractor skill, medium components, and potential water retention. Variation from the design weight can result in structural failure.

The planted roof dead load is independent of other dead loads, such as snow load, included in the guiding building code.

Roof landscaping may change snow drift patterns, seismic loads, and ponding from rain accumulation; these changes may be in excess of typical or previous design allowances. Depending on the type of construction, the climate, and the proposed system, engineers should assess the likelihood that the introduction of a planted roof will have a material impact on other loading.

A planted roof installation can be prematurely rejected for the belief that major structural designs must accompany every retrofit project.

The U.S. Department of Energy reported that most extensive planted roofs often do not require additional structural support: “The weight added by an extensive planted roof is comparable to that of the gravel ballast on a conventional roof— about 15 to 30 pounds per square foot, depending on the growing medium, the depth of the growing medium, and the weight and depth of any additional layers.”3

Consider planting less depth in “weaker” areas or only around columns which might be able to bear additional weight without structural upgrade.

Regional differences

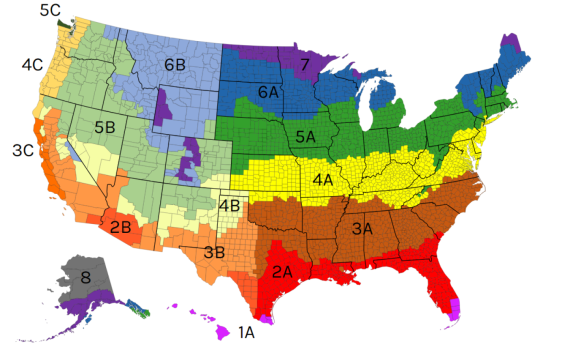

Climate regions from the Department of Energy’s Building America

While the most ideal locations for planted roofs are warm and dry climates, a properly designed roof can thrive in other climates. Each potential project site must be evaluated by an engineer to better predict plant viability and energy performance. Designers can maximize the potential benefits of planted roofs by properly selecting plants, growth medium, drainage layers and other features tailored to the local climate and the building’s surroundings. For more arid climates, see Design Guidelines and Maintenance Manual for Green Roofs in the Semi-Arid and Arid West [PDF].

Remember to consider regional variation in solar radiation when designing a planted roof. The amount of solar radiation can impact plant selection and the viability of installing photovoltaic panels.

High-performance tips and strategies

- Examine the building’s particular micro-climates and orientation to the sun, as well as to other buildings. If there are urban canyons contributing to significant shading or there are high winds, some additional engineering may be required.

- Simultaneous use of planted roofs and planted walls is significantly more effective than the use of planted roofs alone in reducing surface and ambient air temperatures in urban canyons and over rooftops.

- Consider flowering plants to attract pollinators to your planted roof. Learn more about pollinators by visiting Presidential Memorandum on pollinators and the National Strategy to Promote the Health of Honey Bees and Other Pollinators.

- Make sure that the roof has proper structural integrity to support a planted roof.

- Consider the amount of solar radiation as it relates to plant selection and photovoltaics.

- Consider pattern variation instead of homogeneous plantings in order to support different habitats.

- Identify the appropriate stakeholders.

- Make sure that there will be little requirement for supplemental water following the initial plant establishment period.

- Consider the mode of installation, such as delivery in bags via crane.

Resources

Case studies

For more federal case studies, see the Planted roof case studies page.

1 The Benefits and Challenges of Green Roofs on Public and Commercial Buildings [PDF - 9 MB]

2 Green Roof Water Quality and Quantity Modeling

3 Living Architecture: Green Roofs on Public Buildings [PDF - 2 MB]

U.S. General Services Administration

U.S. General Services Administration